The Legacy of Joseph Wagenbach - Comment by Amy Lavender-Harris

Statement for the panel discussion

Goethe-Institut Toronto, September 20 2006

Toronto is a city of narratives that appear and vanish like bicycles weaving in and out of the city’s traffic, like the lights of the CN Tower slicing through a thick fog, or like an elderly neighbour who peers through her curtains every time you pass until one day she vanishes, taking her silence with her.

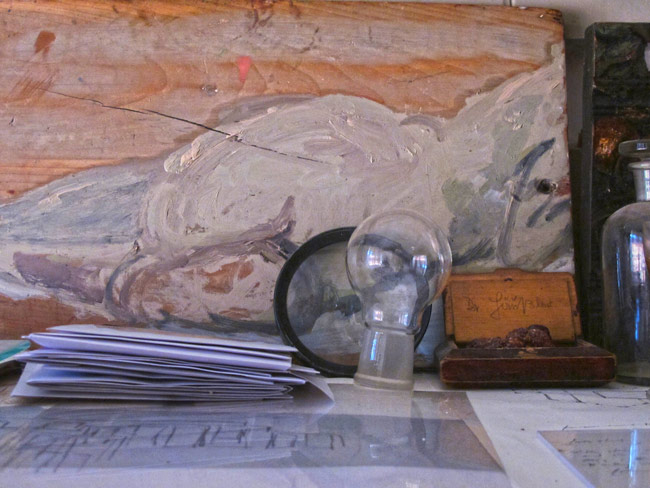

In this city we are ambivalent about eccentricity: houses filled with cats or other collections, homeless shopping bag ladies rumoured to be worth thousands of dollars, a dead man found mummified in his apartment, or a reclusive artist who leaves behind a dwelling filled with disturbing and moving sculptures.

We are ambivalent, not because these eccentrics are really so strange, but because we are both fascinated and frightened to recognise something of ourselves in them. We have our own collections, our own propensity for hoarding objects. We have our own secrets, parts of the past we conceal from our neighbours. We wonder, just a little, whether our own orbit might take us far enough from the centre of things that we, too, will barricade ourselves behind brick and wood, or worse, start enacting who we really are in full view of the entire city. We are never sure which would be worse. And when we encounter these stories - especially about the lives of people at the periphery - we look at them with fascination before almost as quickly looking away, as if there is a contagion associated with them.

In this same way, we treat stories about people like Joseph Wagenbach as object lessons. Through them we catch a glimpse of ourselves, and of our city, out of the corner of our eye. This glimpse is often frightening, and we turn away from it after our initial fascinated voyeurism.

—

Much controversy has been made in the media this week about Iris Haeussler’s mingling of reality and fiction in The Legacy of Joseph Wagenbach. A prominent director of a contemporary art museum reported having felt betrayed by the revelation that Joseph Wagenbach doesn’t actually exist.

I find this controversy perplexing.

I find this controversy perplexing because we are used to reading narratives open-mindedly. When we open the pages of a novel, we enter the possible world of its text knowing full well that it is a product of the writer’s imagination, and yet we are routinely moved by the characters, and we cry or bristle with anger or laugh as if they really existed. We know that novels often expose a deeper truth about who we are, and see them as mirrors of our own souls.

Similarly, when we look at a painting by Dali or a cast by Henry Moore we do not ask, “Is it true?” “Did it really happen?” We know that in an important way it really did.

And sometimes invented narratives – whether in literature or visual art – tell truths about ourselves we could not handle or accept if they were presented as simple fact. They make it possible for us to confront realities we might otherwise turn away from.

—

When we ask why The Legacy of Joseph Wagenbach was conceived as a fictional narrative, we must also ask what it says about us, and about the city we live in. I’ll try to address the second part of the question first, because I think the answer to the first part is wrapped up in it.

In a well known book on urban culture called Soft City, Jonathan Raban wrote that the imagined city is as real, perhaps even more real, than the hard city we can locate on maps. His comment is echoed in Michael Ondaatje’s iconic Toronto novel In the Skin of a Lion. Ondaatje observed that “[b]efore the real city could be seen it had to be imagined, the way rumours and tall tales were a kind of charting.”

We imagine cities. We conjure them into being through the stories we tell about them. We do so because the city as we encounter it – large, chaotic, and hard-edged – is complex and impenetrable until we chart it into coherence by telling stories about it. When we encounter only fragments of other people’s lives – the tread of their footstep, a flash of colour, a muttered word, and incomprehensible behaviour – we construct narratives about them, inventing motives and identities and even histories, in order to fill in the gaps. Jonathan Raban calls this "the grammar of urban life"

And in the places where the grammar of urban life begins to stammer – particularly when we encounter people on the margins – those who are homeless, or derelict, dangerous, or even merely eccentric or reclusive – people about whom we construct unkind caricatures or – worse – about whom we construct no stories at all, we are left with the imaginations of writers, or conceptual artists like Iris Haeussler.

Iris conjured Joseph Wagenbach into being because in this city we lack a narrative that enfolds his experience and his way of being. His story – that of an immigrant who might never have felt comfortable with the culture here, who had suffered almost unimaginable losses but who seemed to have nobody to share them or seek solace with, who settled into a quiet neighbourhood with other immigrants, and who kept to himself, retreating until there was nothing left of him but his sculptures and some clues to build an identity around – is not a story that fits easily with the larger narratives of our Toronto as an open, multicultural city where everybody fits in and is equally visible.

And when we visit Joseph’s house, we are alarmed, and disturbed, and also moved. We begin to realise that Joseph is real, perhaps even more real than some of us in our ordinary, careful passage through the city. We realise that both Joseph and his house are a microsm of the city, of its histories and identities and its grief, and its longing.

And we are reminded of other Josephs, both real ones and invented ones. Because there are both real and fictional precedents of The Legacy of Joseph Wagenbach.

In Robertson Davies’ Toronto novel, The Rebel Angels (1981), the apartments of a reclusive art collector are found upon his death to be filled with paintings and art works, to many they are catalogued and even unwrapped. The reclusive Arthur Cornish, it appeared, hoarded these works and hid them, and himself, from view.

And there are real precedents for Joseph Wagenbach, too. In 2005, a reclusive man named Janos Buda was found dead in his downtown Toronto apartment, his body lying undiscovered for so long that it had mummified. But the most fascinating thing about Janos’ apartment wasn’t that he had died and lain there so long. The most interesting thing was that his apartment was found filled with his own paintings of Toronto scenes and people. Few people had known about this work because he kept to himself. He kept to himself so well that nobody noticed when he died. But the Scarborough Arts Council mounted a show of his works, and efforts have been made to preserve them.

And so we are fascinated with Joseph Wagenbach, just as we are fascinated with the fictional story of Francis Cornish, or with the real story of Janos Buda, or with the urban legends of rich shopping bag ladies and houses filled with newspapers and furniture and cats. And we remember the houses we have seen in downtown Toronto neighbourhoods, such as the house a few blocks away from Robinson Street whose garden is filled with shrouded stuffed animals hung from the trees in plastic bags.

We are fascinated by Joseph Wagenbach, but this time we do not turn away, as we do from cat ladies and crazy old men, and as we did from the story of Janos Buda, erasing it from our minds after our initial, horrified, voyeurism. We do not turn away because we are invited to enter Joseph’s world, to see how he lived, to empathize with his life, and to consider how our own might be a little like it.

—

Iris’ work - her conjuring of Joseph - has invited us to encounter someone else’s life innocently, has invited us to be open to a pure encounter. Had we known of it from the beginning as a conceptual art project, our vision might have been constrained by the drive to interpret Joseph as a work of art, or as a spectacle to which we were audience. But Joseph would have been lost in such a way of seeing. We might not have been able to empathise, and we certainly would not have felt free to invent a narrative of him that was sensitive to his history, to his own losses and longings, to his own need to work out his traumas in his sculptures and collections.

In my view, the great gift Iris has given us is the gift of seeing Joseph Wagenbach, and the city, not just as art but as life.

We care about who Joseph is because we have encountered him as a person rather than as a work of art. And more importantly, we care about Joseph because we have been able to encounter a part of the city that we would otherwise remain closed to experiencing.

© Amy Lavender–Harris