Disclosure (Excavation Notes 01/2009)

These "Excavation Notes" were distributed to all visitors after their guided tours:

The observations noted below start out from a letter apparently received by Mary O' Shea. It was found as one of a set of cylindrical objects in a plain wooden box (Object 4T.27) recovered from the bench inside the concealed chamber. The 32 objects consigned to the box appear to be tightly scrolled sheets of paper, soaked in liquid wax and rolled in earth, which was again partially rubbed off in particular places. We decided to place one of the scrolls into an incubator and remove the waxen skin, to attempt identification.

Our state of excitement, as we are adding piece by piece to the enigma that we have named Mary O'Shea, cannot be understood without considering the situation we encountered in The Grange in 2007. This mansion from 1817 is now Toronto's oldest brick house, situated in the heart of the city, first home to the Art Gallery of Ontario; a mansion that underwent extensive renovations in the 1970s to provide the annex of the Gallery with an aristocratic facelift. Over time, the attic was gutted to make space for modern air-conditioning machinery. The basement floor level was raised by almost half a metre, first by pouring a thick cement subfloor then later by adding a machined wooden floor laid on solid joists. Thus the low ceiling of the basement level was created. It framed the kitchen as a homely, busy space with an almost rural charm, the source for memories of open-hearth cooking and the sweet taste of hand-made cookies for so many visitors. No matter that this space had been empty of original furniture and utensils for decades - it was complemented diligently to the state it might have looked like, from gifts and purchases. Just as the walls were painted as they might have been painted and the floor was covered with a pattern that might have been found in similar historic homes. The main hall received a sweeping, free-standing steel staircase. This grand architectural gesture was deemed more appropriate than the square staircase the Boulton's had built. A curving round wall was set before the bricks of the main-hall's corner, expertly plastered over a metal mesh screen, hugging the rising banister and making space for an alcove. This alcove became the home to Fantachiotti's beautifully seductive "Pandora", a gift the Gallery received in 1924. She stands withdrawn, her marble-white skin exposed to our gazes, contemplating whether the lid on the box in her hand should now be removed.

How could a space like this give rise to the stories we are uncovering?

As the incubator reaches 70°C, the opaque waxen skin that encloses the scroll becomes first buttery white, then transparent. Beads of wax trickle down, collect in a little pool at the bottom of the glass tray. A letter is revealed. Words appear, English words, written with a quill in an untrained but quite legible hand.

[...] you wish to Know the Particulars About your fathers Death I am sorry for to have To tell you He Died on the 27 July 1849 and your Poor Mother About 3 weeks After which was and is a very Great Loss to us. Mary Darby also died also Died a short time after which Left us worse [...]

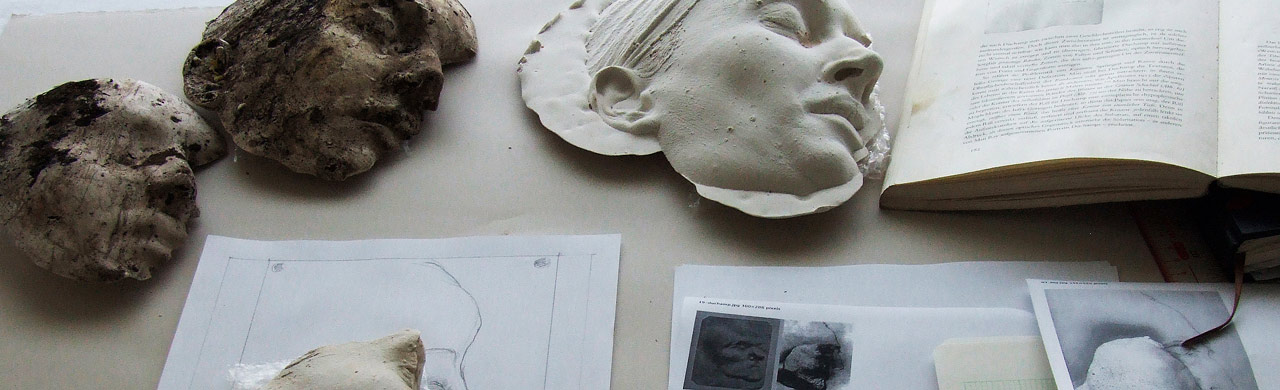

I remember our initial disappointment at the outset of the project, when we encountered such extensive renovations. Our project was predicated on the material substance of Toronto's oldest mansion - it was put in jeopardy where this substance could no longer be made visible. What a joy it was to hold the first "waxen globules" in hand, to knead reference pieces from fragrant wax and spices, to explore the many ways and methods that Mary could have discovered to express herself. But how to link such material evidence to the actual fabric of the historic house?

Excavations began in early August 2008, commencing, as planned, in the 1842 kitchen. It was quickly determined that the wooden floor was not historic, and a small section was removed to assess the subfloor below. We expected dried clay. We found black and white synthetic tiles on a concrete subfloor, most likely work from the 1940s or 50s. Could we remove these? Could we then cut through a section of the foundation slab? We were cautioned that tiles from that time might contain asbestos. A sample was removed and sent for analysis. This was a major setback. Our access to The Grange had already been impeded by the ongoing construction of Transformation AGO. In August we were weeks behind schedule and time was running out to finish the excavation in time for the reopening of the Gallery. A few days later we received the verdict from the Gallery's staff: the floor in the 1842 kitchen was not to be disturbed. Asbestos remediation costs can be exorbitant - and it was unpredictable in what timeframe such work could be completed. But the actual excavation was central to the project, indispensable! This intervention was to provide the link to the roots of the house itself, to the very ground that carried those who lived there, and worked there, and passed through these rooms. Somewhat desperate, I considered alternatives. Could the old Pantry host an alternate excavation site? If so, this would require a major change to the narrative of the guided tours - the sequence of the rooms to visit would need to be reversed: start in the 1817 kitchen, speak about the realities of the maid's life. Then move to the 1840s kitchen. A raised walkway could provide access to the Pantry excavation and thus isolate it from the rest of the basement, creating a hidden recess. It appeared doable. But: would it be possible to open the Pantry floor? Or did the asbestos tiles reach all the way into this part of the building? We cautiously chiselled a probe hole through 20cm of concrete. This time we were in luck. A thin plastic membrane marked the bottom of the concrete slab - and sand was found beneath. The excavation could begin. Expert contractors were called in to remove the foundation slab over the whole room. The concrete was hauled off, we removed the 20cm layer of sand beneath it and finally the clay base I had been looking for lay before us.

[...] we are Badly of Just now and only for your Aunt that Gets the Little washing we Co would not be to gathr Now myself is in the Mill Earning Littel or Nothing your Two sisters is in the Convent School you Poor old Grand Mother sends Her Love and Blessing to you Hoping you will not For Get Her as She Never wanted more [...]

With Amber's biography, I am looking at the fundamental dilemma of immigration in this city of immigrants. Wherever you go, you leave something behind. Thousands of Irish took the path to the Dominions in Amber's time, even more set out for America. The potato had been an unreliable crop in Ireland for years before the famine. The rural population struggled in an exploitative system. Ownership was in the hands of absentee landlords, conditions of tenants were dictated by middlemen who sublet tiny parcels of land, and demanded their rent - not their share - under the spectre of eviction. Unspeakable poverty was widespread, as was unemployment, and housing conditions were appalling. What is the weight of hope for a path out of desperation, when it is burdened upon the shoulders of a seventeen year old, sent to the New World? Would this daughter, this sister, this grandchild send relief? What kind of a burden is that? Does one remember it every morning, with every prayer? What does it feel like - a lump in the throat or a cramp around the middle? Or do you forget it for days, maybe weeks at a time until the next letter arrives? And how does that burden change when that letter carries the news that your relief was too little, too late, too late?

Such questions have little meaning when they are posed in an abstract space of imagined possibilities. It is only when we project them on to the canvas of a material reality, when we give them a name and a face, that we may begin to reflect on what they really mean. But the canvas has to carry the projection, if it collapses easily under scrutiny, the focus shifts from the contents of the story to its construction. The Grange provided the motif, the site-specific aspects, the physical container and the inspiration. I filled in the details.

We found beautiful aged, heritage wood in Hamilton for example; this wood is reclaimed from the weathered barns of the area that are being dismantled over time, hand-hewn planks, studded with square sectioned nails from the local smithy. I used this wood to build the hidden chamber in my studio - just large enough to be accessible, but small enough to hide next to the foundation walls. The shed was then disassembled, transported into The Grange. Amber's hidden space was created there. The basement is damp, it took days and days to apply the plaster coat over sticks I brought from High Park, to let it dry, to paint the walls and blend them into the structure ... Mary's biography had to be completed and aligned with the circumstances of Irish immigration. The artefacts were kneaded, and cast, and layered from wax, fabric, dust, each artifact indeed holds an item of daily life, a time-capsule of discarded little things ... Anthropological Services Ontario was created and given a corporate identity and a Website, the personae of Dr. Chantal Lee, Henry Whyte, the butler, and others appeared in the narrative. Historical research was done, to keep as much of the project as possible close to historical fact - the history of The Grange, the city of York, Ireland; immigration to Canada; other research focussed on archaeological and anthropological practice. Jennifer Rieger - the historic site coordinator of The Grange - was an invaluable, inexhaustible and enthusiastic source of information. And a wonderful, enthusiastic group of volunteers was taken through the process of unlabelled experience, contemplation, disclosure and discussion, and studied the narrative to guide others along a similar journey.

In the end it all came together in time.

We still need to speak of the motif.

My work was created to be experienced as historic fact, as a method for a direct and personal involvement of the visitor. It creates an experience that is not filtered by the categories of contemporary art that we would normally apply to such a tour, it provides a participatory sense of discovery. This principle has been called "haptic conceptual art", a practice that deals with deep questions of the human condition, but initiates them through direct experience, rather than through theoretical discourse.

If this work were labelled as a project of contemporary art, would this protect the visitor, or deny the key experience?

We cannot un-know what we know. We can start from a naive, child-like fascination, then obtain new knowledge about the context, then re-evaluate our experience. But we cannot go through this process in reverse. There is a very large difference between thinking about emotions and actually experiencing them. As we know, a well-written novel, a movie, can be riveting. As we also know, they are no exact substitute for actual presence, involvement, participation. Reality has an edge that imagination lacks. However, finally revealing the fictitious nature of Amber's story - after a time of reflection - is absolutely as much a part of my artwork as constructing the story is in the first place. The point is redirection, not deception.

Therefore I do not place this project as a whole into either category of fact or fiction - it has aspects of both at the same time and it is only as we experience this contrast that we begin to sense how complicated truth is in reality. These are deep questions that I find exciting and I cherish the many different personal reflections I have received on this.

I am grateful to the Art Gallery of Ontario for providing the framework for this historic voyage. It is to the credit of Dr. David Moos, Curator of Contemporary Art at the AGO, that a collaboration was developed in which we both - artist and art museum - were able to break new ground and question pre-existing positions.

The installation will remain in place for the coming months and the narrative will continue to be presented as you have experienced it. It is the starting point for a conversation.

Thank you.

Iris Haeussler