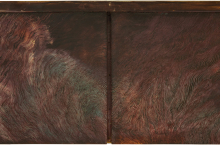

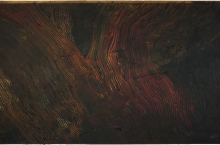

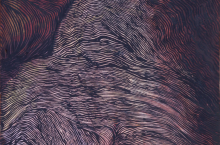

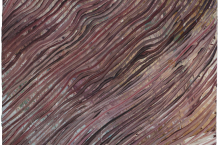

While Florence shared the house and studio with her partner, Sophie La Rosière from 1907 to 1918, she evolved from being a model to an artist herself. It looks like her aesthetics bore a more abstract quality than Sophie’s, and one can imagine the frictions in their relationship as either evidencing their different developments or causing them. What is visible in these paintings seems to foreshadow Florence’s later works on disassembled clothing: a recurring pattern consisting of countless stripes applied in thin brushstrokes beside each other, filling every inch of the painting or object. These strokes seem to have been each executed individually and at times by a trembling hand.

Writer and Curator Philip Monk writes in his essay “Intrapsychic Secrets” not only about the French artist Sophie La Rosière, but also about Florence Hazard. Here is an excerpt of his work:

[...] The breakup between Sophie and Florence was already prefigured, inscribed violently in these few paintings that have been attributed to Florence. Or, at least, comparing Florence’s to Sophie’s paintings, one sees that the couple’s separation was inevitable. It’s all in the paintings. Already there was an antagonism, an irreconcilable difference, rendered aesthetically. Perhaps what could not be said between them came out in Florence’s paintings.[...]

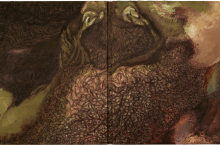

[...] Florence was always potentially a disturbance. She brought the outside inside, first as a liberation, then as a threat. Initially, she gave Sophie greater access to the art world—and the women who inhabited it. But while working as a nurse at the military hospital the Smith sisters established on their estate, she was a daily reminder of the war Sophie wished to shut out. Florence brought in the disturbing pulse of this relentless soul destroying war that upset the erotic balance of the household. This pulse could not be contained and soon infected Florence’s paintings. In fact, this is all they were: a relentless pulse. Her paintings were not obsessive scratches or repetitive neurotic patterns. They subtly registered the shock waves that shook the very bodies of frontline soldiers. They were nothing but this relentless mechanical pulse. Sometimes pulses rippled across the flat surface with the febrile nervousness of Van Gogh’s wheat fields (SLR-236, 238); sometimes their contours shaped themselves into the primitive image of a naked body (SLR-215).

Florence registered the unprecedented shocks of her time in such a way that could not be cloistered or hidden away behind private, domestic pleasures. Her paintings were sensitive recording devices so aligned to the new graphic recording systems of the scientific experiments in physiology of her time. Her entire body registered this pulse she then directly transferred to her paintings. This was a matter of the whole body and not just the genitalia; it was the shock of the actual, not the representation of a symbol. Note that the sexual organs aren’t even articulated in Florence’s paintings (see SLR-215).

Even if she had tried, Sophie would not have been able to entomb Florence’s paintings. They would have resisted. After all, Florence’s paintings represent something else, being essentially of a different nature. It is not so much the couple’s paintings that oppose each other, the one erotic and quasi-spiritualized, the other mechanical and quasi-materialist. Rather, their contrary entombing and pulsating answer to different regimes of logic. Sophie’s entombed paintings adhere to the theological logic of the negative whereby wax maintains an imprint of memory in a meeting of “sensible surfaces”.[i] Florence’s paintings depend on the positive logic of relay whereby ghostly sensations are transmitted. Such transmission render a surface vibratory in order to imprint a pulse, not reproduce a surface. They flash hidden affects rather than bury obscured secrets.

(“Traditionally, the arts of copying had been enshrouded with an aura of magic or theological mystery. The logic of the negative—wax to seal, cast to form, stone to print—carried with it the enigma of parentage, of the transmission of physical and, usually, optical resemblance to another object, upon which the imprint remained stored as memory.… Copying therefore referred not to a merely material process but to a meeting of sensible surfaces, a matrix where internal properties and external regimes coincided. Hence, whether in its secular or theological formulations, copying or mechanical inscription signified an ontological relay, or in André Bazin’s characterization of the photographic image, as a ‘transference of reality from the thing to its reproduction’.”) Brain, Robert Michael, The Pulse of Modernism: Physiological Aesthetics in Fin-de-Siècle Europe, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2015, pp 9–10.